realMyst: Masterpiece Edition (5/5)

When I was about twelve years old, the family of my best friend owned a copy of Myst that we would occasionally fire up and try to play. I’m not sure who else actually played the game, but someone must have, because whenever we loaded the latest saved game, more progress had been made. Unfortunately, we could never really get anywhere with Myst, and mostly we just sort of pushed buttons and wandered around while enjoying the view. At the time it was the video game equivalent of a walk through the woods or a lazy Sunday drive through the countryside. Despite not actually doing much, there was a certain appeal in just spending some time exploring the world of the game.

When I was about twelve years old, the family of my best friend owned a copy of Myst that we would occasionally fire up and try to play. I’m not sure who else actually played the game, but someone must have, because whenever we loaded the latest saved game, more progress had been made. Unfortunately, we could never really get anywhere with Myst, and mostly we just sort of pushed buttons and wandered around while enjoying the view. At the time it was the video game equivalent of a walk through the woods or a lazy Sunday drive through the countryside. Despite not actually doing much, there was a certain appeal in just spending some time exploring the world of the game.

The fact that my friend’s family owned a copy of Myst speaks to its position within the evolution of technology and culture in the 90s. During that decade, computer tech was becoming mainstream, moving from the world of geeky hackers seen in films like Wargames into an aestheticized product sold by Apple as much for what their products could do as for how their products looked. At the time, Myst’s graphics were quite impressive, and families bought the game as much to play as they did to showcase their swanky new PC’s abilities. In this sense, Myst became an item of bourgeois respectability, something that probably hurt the game’s reputation in the long run.

I never beat Myst back in the 90s, but since I first aimlessly moseyed around its abandoned landscapes, I became a fan of adventure games, starting with LucasArts’s run of 90s classics and later moving on to today’s incredible indie game riches in the genre. I recently decided to return to the adventure game classic, which held the title of best selling game for nearly a decade. Instead of playing the original, however, I picked up realMyst: Masterpiece Edition, a revamped sort of director’s cut. RealMyst boasts of improved graphics, weather, cycles of day and night, a flashlight, an extra world to explore, and, perhaps most excitedly, the ability to walk through the worlds of Myst rather than just click your way through like a slideshow. But if you prefer (and I did), you can choose to click your way around the environments like in the original release. But even if you choose to navigate the old fashioned way, you can see the camera repositioning itself instead of just being replaced with a new scene.

You start Myst on a small island filled with mysterious objects and structures, including a sunken ship, an observatory, a clock tower, a library, and a rocketship. There are no instructions, no prelude that tells you what to do and how to do it. Instead, you must play around with various machines on the island in order to figure out what next steps to take. What thin narrative that does exist in the game involves two brothers, Sirrus and Achenar, who have been trapped within a red book and a blue book, both of which you discover in the library. Speaking through static, each brother claims that the other is responsible for their father’s death, and in order to release them from their prison, you must collect pages littered throughout various lands that connect to Myst Island.

From here, you’re off, using the various buildings and machines on Myst Island to find books that connect to various other lands, or ages, where you must search out red and blue pages to bring back to the brothers as well as discover the exit from each age back to Myst Island. The set up for the game is actually reminiscent of the original Legend of Zelda where you returned to the main map after discovering a piece of the triforce in each dungeon. This simple quest structure shows some of the game’s age. For instance, you can’t carry both pages, so once you’ve returned one page to one of the brothers, you have to head right back into the same age to retrieve the second page, retracing most of your steps. When you do finally return the pages, the brothers don’t really provide you with much more backstory. They mostly repeat what they have already said and, like an addict, beg for more pages.

We learn most about brothers Sirrus and Achenar from their rooms you find in each age. Achenar’s rooms are filled with images of death and torture. And while Sirrus’s rooms at first appear to be the product of a more refined taste, you quickly realize that he has an insatiable greed and has been plundering each age where he has set up shop. But Myst isn’t about narrative. Sure, there’s a story and a fairly robust mythology if you’re willing to read through various materials, but the joy of Myst is exploration, the simple time it takes to wander around each world and solve puzzles.

This time around, I didn’t find the puzzles to be all that difficult. A steady diet of adventure games has likely made the game easier, and I’m hopefully a bit smarter today than when I was twelve. Most puzzles involve you futzing around with various machinery, figuring out how they work and interact with the rest of the world. That doesn’t mean the game is a breeze. It takes some mental sweat, and I resorted to hints on two occasions. Also, the Selenitic Age, whose theme is sounds, is still a pain in the ass. I used up one of my hints on its confusing labyrinth, the most dreaded of all adventure game puzzles.

This time around, I didn’t find the puzzles to be all that difficult. A steady diet of adventure games has likely made the game easier, and I’m hopefully a bit smarter today than when I was twelve. Most puzzles involve you futzing around with various machinery, figuring out how they work and interact with the rest of the world. That doesn’t mean the game is a breeze. It takes some mental sweat, and I resorted to hints on two occasions. Also, the Selenitic Age, whose theme is sounds, is still a pain in the ass. I used up one of my hints on its confusing labyrinth, the most dreaded of all adventure game puzzles.

As a mature adult, I found Myst’s puzzles more enjoyable than frustrating, but the real reason to play Myst are the landscapes. In addition to Myst Island, there are five ages, including the Mechanical Age, Stoneship Age, Channelwood Age, the aforementioned Selenitic Age, and the Rime Age (a bonus level tacked on to the end of realMyst). The worlds of Myst incorporate steampunk visuals. The Mechanical Age takes place on an island that’s also a giant gear; the Stoneship Age takes place on a jagged rock with a ship stuck in the center of it; and the Selenitic Age looks like the landscape of Mars from some 1950s b-movie. Overall, the technology of the worlds are decidedly analog.

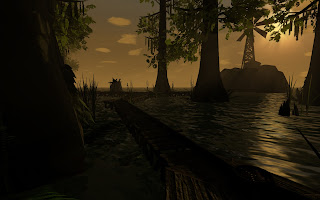

My favorite age is Channelwood, which looks like someone took the Ewok village from Return of the Jedi and transported it to a Florida swamp. There are two levels in Channelwood, one a series of wooden walkways snaking their way among tall trees, and the other, reachable by hydraulic-powered elevators, a series of rooms and bridges among the tops of the treeline. Like most of the places in Myst, there’s something inviting about Channelwood. It’s the impossible treehouse you wish you had as a kid.